Deconstructing Markale II

November 12, 2013

Written by: Andy Wilcoxson

At 11:10 AM on 28 August 1995 a 120 mm mortar shell landed near the Markale Market in Sarajevo. The explosion killed 38 people and

wounded another 75. The Bosnian-Serbs were blamed for the attack, although they

denied responsibility, and NATO air strikes were launched against Bosnian-Serb

targets.

The

Muslims allege that the Serbs shelled the Markale

Market in order to terrorize the civilian population. The Serbs allege that the

Muslims shelled the Market themselves in order to give NATO a pretext to launch

its bombing campaign.

The

UN Protection Force was dispatched to investigate the incident and they,

together with the local police, initially concluded that the fatal round came

in at a bearing of 170 degrees. However, in their final report they concluded

“beyond reasonable doubt” that the mortar round was “fired from Bosnian Serb

territory … from the Lukavica area at a range of between

3,000 and 5,000 meters … the bearing of this round was most likely from 220-240

degrees.”[1]

Two

separate trial chambers at the ICTY also concluded “beyond reasonable doubt”

that the shell was fired from Bosnian Serb territory – but not from Lukavica.

According

to the Dragomir Milosevic judgment, “The mortar shell

that struck the street in the vicinity of the Markale

Market was fired from the territory under the control of the SRK [Sarajevo-Romanija Corps of the Bosnian Serb Army] and it was fired

by members of the SRK ... the Trial Chamber is persuaded by the evidence of the

BiH police, the UNMOs and the first UNPROFOR

investigation, which concluded that the direction of fire was 170 degrees, that

is, Mount Trebevic, which was SRK-held territory.”[2]

The

Perisic trial chamber came to the same conclusion:

“The Trial Chamber finds beyond a reasonable doubt that on 28 August 1995

shortly after 11:00 hours, a 120mm mortar shell hit the entrance of the City

Market on Mula-Mustafe Baseskije

street killing 38 persons and injuring 75 persons. The

Trial Chamber also finds that the mortar shell was fired from the VRS-held

territory on the slopes of Mt. Trebevic.”[3]

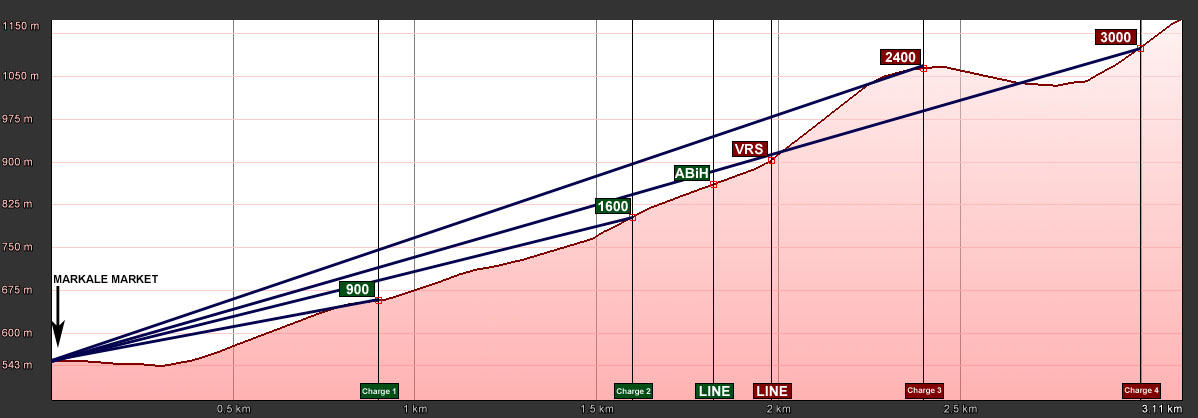

The

judges were persuaded by the evidence of the prosecution’s mortar expert,

quartermaster sergeant Richard Higgs of England. Higgs identified four possible

firing positions along the 170 degree bearing where the mortar could have been

fired from: 900, 1600, 2400, and 3000 meters from the market depending on the

propulsion charge used to fire the mortar. He concluded that 2400 meters was

the most likely firing position.[4]

Anyone

capable of reading a map can see that Lukavica and

Mt. Trebevic are in two completely different

directions. Lukavica is to the west and Mt. Trebevic is to the south of the Markale

Market. UNPROFOR’s investigation concluded “beyond a reasonable doubt” that the

shell was fired from Lukavica, but two ICTY trial

chambers have found “beyond a reasonable doubt” that it was fired from Mt. Trebevic.

The

only thing you can conclude beyond a reasonable doubt is that the ICTY’s

findings and UNPROFOR’s investigation can’t both be right. Either UNPROFOR is

wrong, the ICTY is wrong, or both of them are wrong.

Mapping

the ICTY and UNPROFOR’s Claims

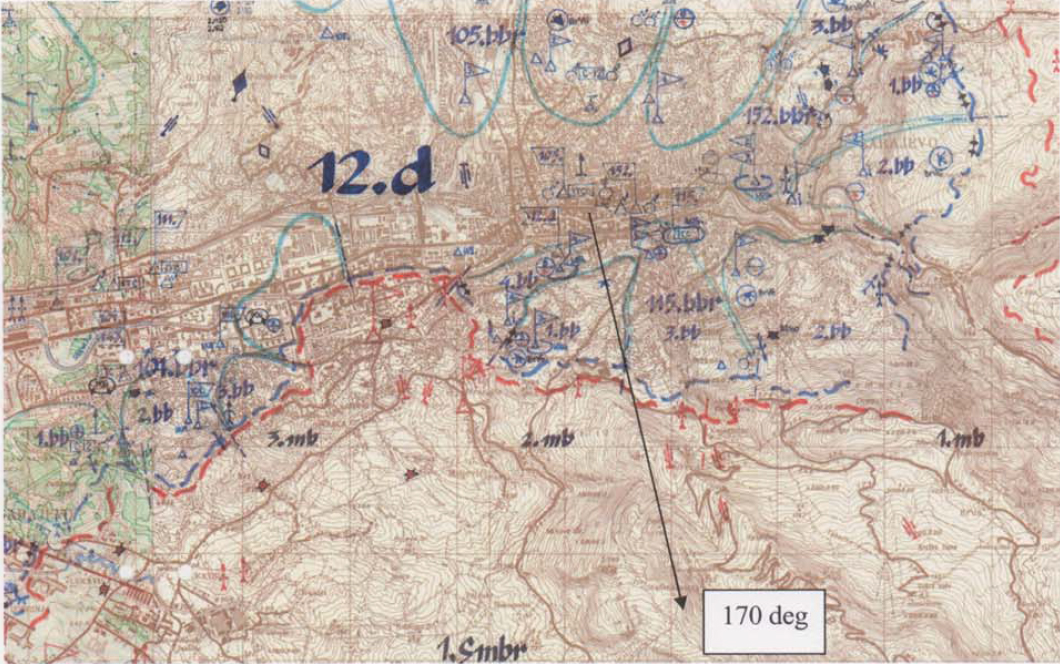

This map shows the frontlines around Sarajevo, the firing positions alleged by

the ICTY and UNPROFOR, the location of the UN Observation post, the findings

from QMS Higgs report and a circle with a 1,050 meter radius centered on the Markale Market. In order to understand the rest of the

article, I would urge the reader to take a minute and get acquainted with the

map.

ICTY

& UNPROFOR: Getting the Location of the Front Lines Wrong

In

order to determine whether the shell was fired from the Serbian or the Muslim

side of the confrontation line it is important to know the location of the

front lines.

Even

though the ICTY and UNPROFOR don’t agree on the direction that the shell came

from they both agree that the confrontation line was 1,050 meters away from the

Markale Market.[5]

In

reality, the front lines were much farther away than the ICTY or UNPROFOR say

they were. The Serb lines were about 1,700 meters away in the direction of Lukavica and about 1,900 meters away in the direction of

Mt. Trebevic.

Moving

the confrontation lines closer to the market than they actually were reduces

the area from which the Muslims could have fired the shell and increases the

area from which the Serbs could have fired it. Manipulating the location of the

confrontation lines makes it appear more likely that the Serbs fired the shell

and less likely that the Muslims did.

The

blue circle on the map has a radius of 1,050 meters and is centered on the

impact crater. As you can see the circle comes nowhere close to the front

lines.

Hear

No Evil

A

lot has been made of the fact that one of the UN Military Observers assigned to

the UN Observation Post didn’t hear any outgoing mortar fire.

According

to the Dragomir Milosevic judgment, “The UNMOs Lt.

Com. Thomas Knustad and Maj. Paul Conway were posted

at OP-1 and they heard an impact and explosion after which they observed smoke

coming from the area of Markale, about 2,000 metres from where they were. Lt. Com. Knustad

was confident that the round, which resulted in the explosion that he heard and

observed from his post, was not fired from within his area of responsibility.

Lt. Com. Knustad estimated that the maximum distance

at which a 120 mm mortar shell can be heard is at least four to five kilometres. He therefore excluded the possibility that the

shell was fired from within ABiH-held territory

because he would have heard it.”[6]

It

is highly interesting that the trial chamber only heard testimony from Knustad, but not Conway. It is especially interesting

because Conway was at the observation post and Knustad

wasn’t when the incident occurred.

According

to the Perisic judgment, “At about 9:00 hours on 28

August 1995, UNMOs Thom Knustad from Norway and Paul

Conway from Ireland assumed their duties at OP-1. It was a bright, sunny

morning and Knustad was sitting outside the house

while Conway was at the observation post. At about 11:00 hours, Knustad saw a smokestack coming up from what he instantly

identified as the Markale area and then heard the

impact about five to six seconds later. Knustad

joined Conway at the observation post, where they recorded the incident in the

log book kept there and Conway immediately reported the incident to the UNMO

headquarters at the PTT building.”[7]

Incredibly,

nobody bothered put Paul Conway, the UNMO who was actually on duty at the

Observation Post at that exact moment, on the witness stand until 2012 when

Radovan Karadzic called him to testify as a defense witness.

Once

Conway took the stand it was obvious why the Prosecutor hadn’t called him to

testify. He said that he wasn’t sure if the explosions he heard were the sound

of mortars impacting the Markale Market or if they

were the sound of outgoing mortar fire.

Conway

testified that he heard the sound of “muffled explosions.”[8] In response to questioning from the

Prosecutor he said, “I was always confused as had I heard outgoing or incoming.

So I can't say that I only heard impact. I don't -- to be honest, I don't know

what the explosions I heard were coming from.”[9]

The

prosecutor put it to Conway that “the sound of 120-millimetre mortar firing is

not - to use your word – ‘muffled’ if fired from a reasonably close distance to

the listener” and he agreed saying, “I would expect it to make a very

distinctive ‘vrmph’ and ‘trmph’

and you'd know that a heavy explosion had occurred.”[10]

The

Prosecution’s Mortar Expert

As

previously mentioned, the Prosecution enlisted a British mortar expert named

Richard Higgs to determine the possible firing positions for the mortar that

hit the Markale Market.

According

to his report, “At an angle of [descent] approximately 70 degrees the different

possible charges give ranges in the following areas;

“Charge

1 = 900m

“Charge 2 = 1600m

“Charge 3 = 2400m

“Charge 4 = 3000m

“When

you take into account where these plot on a map, the fact that the UN observers

did not hear the round being fired and the shallow crater the following

assumptions can be made. At a range of only 900m would put the firing position

inside the confrontation line and in direct line of sight and ear shot with the

UN observation post which would only have been approximately only 1km away. At

this distance they would have heard the round being fired.

“At

a range of 1600m places the firing point is in the area of the confrontation

line but still in easy ear shot of the UN observers. At a range of 2400m puts

the firing position in the hills which is out of ear shot of the UN observers

due to the lay of the land i.e. they would not have heard the round being fired

due to the hills and valleys. This area is also one that is marked next to a

gun position on the confrontation positional map.”[11]

Higgs

further elaborated on his findings in court. He said, “If the round had been

fired from 900 metres, this puts that location very

close to an urban area where there would be lots of people who could have heard

the firing, and there was no report that anyone heard that firing. Then when

you come back to 1600 metres it places it right

between the confrontation lines, which would be totally tactically sound (sic)

for the position of a mortar and again very close in direct line of hearing

from the UN observer, so you should have heard it. And then when you back to

the area of 2400, you are now coming back to the more ideal position where a

mortar would want to be, on the higher ground. It is far enough away from the

confrontation line for tactical reasons for survivability. Plus, because it is

up there in the hills, steep hills, it is shrouded from the UN observer by

these hills, and so therefore, of course, that would reduce the chance of any

sound being heard when fired.”[12]

The

Prosecutor asked Higgs to explain why he eliminated the 1,600 meter firing

position, and Higgs replied, “That position there would put this particular

mortar either right on the front line or even in between the two front lines.

For such a valuable asset, to place it in such a vulnerable position would not

make tactical sense. The 120-millimetre mortar is a large piece of ordnance.

Its ammunition is heavy. Ideally it is resupplied by a vehicle or many, many

people; and to place it in that location just would not be sensical.”[13]

Higgs

said that it was his firm conviction that the mortar had been fired from a

distance of 2,400 meters, and when the Prosecutor asked him if the mortar crew

could see the marketplace from 2,400 meters he said, “From that area, you

cannot see the market itself because it is hidden by the taller buildings all

around it. But you can identify the taller buildings very easily. For instance the

cathedral is not far from that location and the other taller buildings. So you

could use those as reference points to assist you, but you cannot see the

marketplace itself.”[14]

There

are a number of problems with Higgs’ evidence. The first problem is the fact

that claims that the UNMOs at the observation post hadn’t heard any outgoing

fire, when we know that UNMO Conway did hear something but he isn’t sure what

he heard. But to be fair, Higgs testified before Conway did and so he couldn’t

have possibly known what the UNMOs heard, even though he may have thought that

he did based on the information provided to him by the prosecutor.

The

next problem is that Higgs eliminates the 900 meter firing position as a

possibility because he says nobody reported having heard a mortar being fired.

If somebody did hear that, they likely would have reported it to the police in

Sarajevo, and if the Muslims had done the shelling themselves to blame the

Serbs and provoke a NATO intervention, would they have passed along those

reports to Higgs or the ICTY? Probably not.

Moreover,

the sound of mortars being fired was commonplace in Sarajevo during the war. A

person in the city who heard the sound of mortar fire would probably have

assumed that it was being fired at the Serbs and they wouldn’t have paid any

mind to it. They wouldn’t necessarily have connected the sound with the attack

on the Markale Market and reported it.

Another

problem with Higgs’ evidence is that he eliminates the 1,600 meter firing

position because he thinks it is right on top of the confrontation lines.

Unlike the trial chamber itself, and unlike UNPROFOR, at least Higgs knows

where the confrontation lines are at. Higgs’ problem was that he didn’t know

where the market was at as evidenced by this map from his report.

The reason why Higgs thinks that 1,600 meters is right on top of the

confrontation line is clear from the map in his report. His map makes it

obvious that he started measuring from the wrong place. His map puts the

location where the mortar impacted about 240 meters away from where it actually

did. He put the crater closer to the confrontation line so that when he

measured 1,600 meters he found himself right on top of the confrontation line

instead of being more than 200 meters inside of Muslim territory like you would

if you measured from the real impact site.

And

to compound that error he miscalculated magnetic declination when he plotted

the 170 degree line on the map. According to NOAA, the magnetic declination in

Sarajevo was 2.22 degrees east on 28 August 1995, but Higgs has the line drawn

as if magnetic declination were 3.25 degrees west and so the line he drew not

only starts from the wrong location, but the bearing of his “170 degree” line

is off by more than 5 degrees.

According

to Higgs, a Serbian mortar crew at 2,400 meters would have seen buildings in

the city that would help them target the market, but he says the terrain would

have blocked the sound of the outgoing mortar fire from reaching the UN

Observation Post, and he notes in his report that there is a Serbian gun

position on the map at about 2,400 meters distance from the market.

Contrary

to what Higgs claims, there is perfect line of sight between the Serbian gun

position at 2,400 meters and the UN Observation Post. There are no buildings

and no terrain that would block or muffle the sound of outgoing mortar fire

from reaching the Observation Post. The sound would have been clear as a bell.

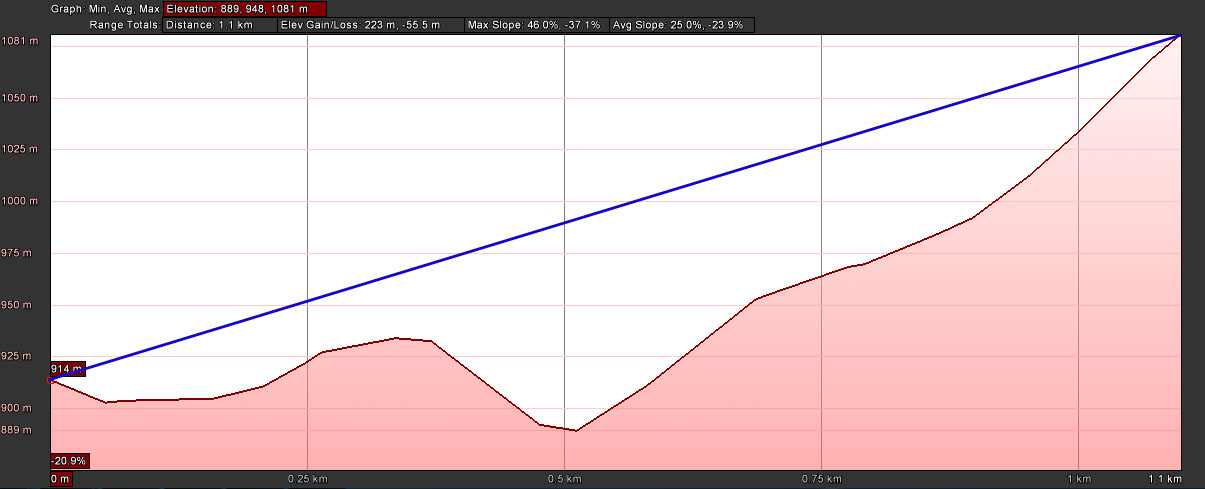

This diagram is an elevation profile showing the terrain between the

Observation Post on the left and the 2,400 meter Serb gun position on the

right.

At 3,000 meters there is no line of sight to the Observation post, but there is

also no line of sight to the city. A mortar crew at 3,000 meters wouldn’t have

been able to see the city in order to target the market. At 3,000 meters there

is no line of sight to the Observation post, but there is also no line of sight

to the city. A mortar crew at 3,000 meters wouldn’t have been able to see the

city in order to target the market. The diagram below is an elevation profile

showing the line of sight from each of the potential firing positions to the

market.

When

Higgs dismissed the 900 meter firing position in his report he said, “At a

range of only 900m would put the firing position inside the confrontation line

and in direct line of sight and ear shot with the UN observation post which

would only have been approximately only 1km away. At this distance they would

have heard the round being fired.”

As

you can tell from the map, the observation post was half way up the hill. It

was northeast of the 900 meter firing position and southeast of the 2400 meter

firing position. The distance from the Observation Post to the 2400 meter

firing position is practically the same as it is to the 900 meter firing. Higgs

cannot credibly argue that outgoing mortar fire would have been audible to the

Observation Post at 900 meters from the market, but not at 2400 meters.

The

1,600 meter firing position, which Higgs dismissed because he started measuring

from the wrong place, would have put the mortar crew in Sarajevo’s Bostarici neighborhood, which was held by the Muslims.

From

Bostarici a mortar crew would have had a good view of

the city, and unlike the forested slopes of Mt. Trebevic,

there are buildings in Bostarici that could deflect

and muffle the sound. In fact, there is even a hill in the eastern part of Bostarici that would have prevented the observation post

from having line of sight into certain parts of the neighborhood.

As

Higgs noted in his testimony, “The 120-millimetre mortar is a large piece of

ordnance. Its ammunition is heavy. Ideally it is resupplied by a vehicle or

many, many people.” As one can see from Google’s satellite imagery, there

aren’t a lot of roads on the top of Mt. Trebevic, but

there are paved roads in Bostarici.

It

is important to be fair to QMS Higgs. His report does say, “It must be

remembered that I only have the evidence of others to go by and must make my judgements based on the facts in front of me.” The

inaccuracies in his report may be attributable to bad information he received

from the Prosecution.

ABiH Use of Mortars in

Sarajevo

It

is noteworthy that the ABiH and the VRS both had 120

millimeter mortars in their arsenal and that the ABiH

troops in Sarajevo were very skilled at firing their mortars and moving them

quickly.

Major

Roy Thomas was the senior UNMO in Sarajevo from 14 October 1993 until the 14th

of July, 1994. Major Thomas has 35 years of military experience with the

Canadian Armed Forces. And prior to his arrival in Sarajevo, he had

participated in five UN peacekeeping or military observer tours.

Major

Thomas testified for the Prosecution in the Radovan Karadzic trial, and during

his cross-examination, Maj. Thomas explained that “Some of the Bosnian [Muslim]

tactics proved to be superior, and one of them, I think, deserves some look by

military analysts, not necessarily in this court, is how they managed to use

the mortars and get them moved so quickly and avoid any semblance of

counter-battery fire on your [the Bosnian-Serbs’] part.”[15]

Major

Thomas told the court, “I'll tell you the most novel use of transport was a

mortar that was put in an unused railway car near the PTT building, was pushed

out by people on foot. It fired and then was pushed back before the Serb

artillery reacted.”[16]

The

ABiH mortar crews were also skilled at concealing

their activities from the UNMOs. Maj. Thomas told the court that UNMOs in Sarajevo

“spent a lot of time trying to catch them moving mortars into the hospital

grounds and then firing and then moving, but we were never able to pick them up

doing it. But we know they did it.”[17]

Maj.

Thomas wasn’t the only UN official to testify about the ABiH’s

use of mortars in Sarajevo either. A senior French military official who had

been deployed with the UN in Sarajevo also testified for the prosecution under

the pseudonym of KDZ-185.

Witness

KDZ-185 told the court: “I underline that the mortar units, especially with the

Bosnians, had this characteristic, that they would move them very often. They

had no fixed position, which accounts for the fact that unlike the Serb

artillery positions, we had not ascertained what the permanent locations were

of the Bosnian mortar units because such did not exist. They would move them

frequently so as to avoid being located and have a counter-battery fire fired

on them.”[18]

It

wasn’t just UN Personnel who saw the ABiH moving

their mortars around the city either. Martin Bell was a journalist who covered

the war for the BBC, and he testified in the Karadzic trial that he saw them

firing from mortars mounted on vehicles. Karadzic asked him: “Do you recall

that there were mortars mounted on vehicles, and they moved around the city and

opened fire from various locations?” And Bell responded, “Yes, Dr. Karadzic, I

saw that for myself.”[19]

In

light of the fact that the Bosnian-Muslims were adept at moving their mortars

quickly and firing them without being detected by the UN it is not beyond the

realm of possibility that a Bosnian-Muslim mortar crew could have opened fire

on the market from a location in Bostarici, out of

sight of the UN Observation Post, and gotten away without being detected.

Bostarici, Caco, and the 10th Mountain Brigade

During

the first part of the war, Bostarici was controlled

by the 10th Mountain Brigade commanded by a notorious Muslim warlord

named Musan Topalovic --

better known as “Caco” (pronounced ZA-tso).[20]

David

Harland was the head of UN civil affairs in Bosnia during the war. According to

his testimony at the ICTY Caco was “a dangerous man”

he said that “his whole unit was engaged in violence” and that “Caco, of course, had not only been killing Serbs; he had

been killing Muslims as well. And I think, in fact, the action which led to his

own death was a last spasm of violence in which he had killed a number of

Muslims.”[21]

General

Vahid Karavelic of the ABiH testified in the Delic trial

that they were afraid that outlaw units like Caco’s

10th Mountain Brigade would “attack us from the back.”[22] Indeed, the 10th

Mountain Brigade would ambush other units of the ABiH

and steal their equipment.[23]

In

late 1993 the Bosnian authorities killed Caco,

disbanded the 10th Mountain Brigade, and put Bostarici

under the control of the 115th Brigade, but Caco’s

men remained.

When

Caco was killed the New York Times reported that

“senior police officials said killing Mr. Topalovic

and arresting Mr. Delalic, the other gang leader,

would only dent the power of the gangs.

“’We

got the big Caco,’ a senior officer said, using the

dead gang leader's nickname. ‘But there are lot of little Cacos

waiting to take his place, and as long as we are in this situation, the

criminals will always be on top.’”[24]

Regardless

of their behavior, Caco’s men were seen as valuable

fighters by the Bosnian Government. The Bosnian-Muslim authorities were even

willing to look the other way when Caco attacked

their own police.

According

to one report in the New York Times, “A militia group led by a 29-year-old

former nightclub singer known as Caco attacked three

police stations, seizing 30 officers and taking them off to dig trenches at the

front-line positions held by Caco's men on Trebevic mountain ... ‘This is being handled very gently

because these guys are very good on the front line,’ said Ejup

Ganic, a vice president, referring to Caco's men. His view, as well as being expedient, reflected

a widely held opinion: that militia leaders like Caco,

even if they behave like renegades, have permitted the city to resist the

Serbs.”[25]

When

the Bosnian-Muslims killed Caco, the New York Times

reported that “The crimes that Mr. Topalovic and his

followers are said to have committed made the Government's failure to take

action sooner all the more striking. Mr. Alispahic,

the Interior Minister, said the gang leader's activities included seizing

people from their homes and killing them; seizing women at gunpoint to be

raped; kidnapping wealthy people in Sarajevo and holding them for ransom

payments of as much as 100,000 German marks, about $60,000; blackmail of other

well-to-do people, also for large sums, and grabbing men off the streets and

forcing them to dig trenches at the front.” The report also noted that “Mr. Topalovic broke into a funeral home used for many of the

victims of the siege and robbed its owner of 400,000 marks, about $240,000.”[26]

Just

because Caco was killed it didn’t mean that his men

disappeared. After he was killed, the Agence France Presse wire service reported that “a number of Caco supporters were still believed to be hold up in houses

close to his former command post.”[27]

According

to press reports, Caco had some 2,800 men under his

command.[28]

In 1996 thousands of his men turned out for his funeral. Agence

France Presse reported that “In a remarkable show of

solidarity, thousands of men, many of them former comrades in arms, flooded the

narrow streets of the old Turkish district of Sarajevo to pay their last

respects to Caco on Saturday.

“Caco's body was passed from hand to hand in traditional

fashion all the way from the mosque to the Kovaci

cemetery, a distance of one kilometer.”[29]

The

Kovaci cemetery where Caco

is buried, otherwise known as “Martyrs’ Memorial Cemetery,” is the

Bosnian-Muslim equivalent of the Arlington National Cemetery. It is the

cemetery where they bury their most honored veterans.

The

fact that Caco was killed in the autumn of 1993,

doesn’t mean that some of his men weren’t still lingering around Bostarici in the summer of 1995 when the Markale Market was hit. The fact that they were still

around for his funeral in 1996 is a good indicator that they were there in 1995

too.

This

was a depraved group of criminals and thugs who raped, robbed, kidnapped, and

murdered Serbs and Muslims alike. One cannot lightly dismiss the possibility

that they may have been the ones who shelled the Markale

Market especially when the heading that the shell came from points to an area

where they were known to be active.

As

the ballistics show, the Bosnian-Muslims had the means and the opportunity to

shell the Markale Market, and they had a motive.

The

motive was to incite international outrage against the Serbs, who would be seen

as responsible. The logical assumption when a shell is fired into Sarajevo is

that it must be the Serbs surrounding the city who did it. By shelling the Markale Market, the Muslims could exploit the carnage to

motivate NATO retaliation against the Serbs.

If

the Bosnian-Government wanted “dirty work” to be done, then Caco’s

men would have been the logical people to turn to. They were immoral and

unscrupulous cut-throats who could have easily been bribed to do anything.

In

spite of the ICTY and UNPROFOR’s findings, there is ample room for reasonable

doubt to make a definitive conclusion about who fired that shell.

[1]

D. Milosevic Exhibit P00357

[2]

D. Milosevic judgment, paras 724, 719

[3]

M. Perisic Judgment, para. 467

[4]

Ibid.

[5]

D. Milosevic Ex. P00357, Pg. 21; M. Perisic Judgment para 448; D. Milosevic Judgment para 693

[6]

D. Milosevic Judgment para 690

[7]

M. Perisic Judgment para 443

[8]

R. Karadzic Exhibit D2329

[9]

R. Karadzic Transcript, 17 October 2012; pg. 29013

[10]

Ibid., pg. 29011

[11]

R. Higgs Expert Report; D. Milosevic Exhibit P588.

[12]

D. Milosevic Transcript, 24 April 2007; pg. 5026-5027

[13]

Ibid., Pg. 5028

[14]

Ibid., Pg. 5029

[15]

R. Karadzic Transcript, 15 September 2010, pg. 6831

[16]

Ibid., Ibid., pg. 6841

[17]

Ibid., Ibid., pg. 6842

[18]

R. Karadzic Transcript, 29 June 2010, pg. 4283

[19]

R. Karadzic Transcript, 15 December 2010, pg. 9872

[20]

Testimony of Asim Dzambasovic,

Testimony of Asim Dzambasovic, R. Karadzic Transcript, 22 June 2011, pg. 15224

[21]

D. Milosevic Transcript, 16 January 2007, p. 445-446

[22]

R. Delic Transcript, 26 March 2008, pg. 7884

[23]

R. Delic Exhibit 00392e

[24]

The New York Times, "New Horror for Sarajevo: Muslims Killing Muslims", October 31, 1993

[25]

The New York Times, "Renegades Help Bosnia By Helping Themselves", July 5, 1993

[26]

The New York Times, "New Horror for Sarajevo: Muslims Killing Muslims", October 31, 1993

[27]

Agence France Presse, "Serbs shell Sarajevo district controlled by renegade brigade", October 28, 1993

[28]

Press Association, "Sarajevo Streets Ruled By Rogue Commander," June 3, 1993

[29]

Agence France Presse, "Sarajevo re-buries a war legend," November 02, 1996

Presse, November 02, 1996 02:18 GMT

If you

found this article useful please consider making a donation to the author by

visiting the following URL: https://www.paypal.com/cgi-bin/webscr?cmd=_s-xclick&hosted_button_id=AYU7SP3575BSQ