Srebrenica: The Ugly Truth

Written By: Andy Wilcoxson

11 July 2014

Genocide is understood by most to be the gravest of all crimes against humanity. Few words in our language are more emotive, more inflammatory, or provoke the same furor.

Genocide is precisely the crime that Bosnian-Serb leaders stand accused of in connection with the July 1995 Srebrenica massacre.

Anthony Lewis’ reporting is a typical example of the Western news media’s coverage. This Pulitzer Prize winning journalist told readers of the New York Times that “The Bosnian Serb leaders were not on the scale of the Nazis, but the evil was the same. General Mladic presided over the slaughter of 8,000 civilian men and boys after his troops captured the U.N. safe haven of Srebrenica.”[1]

In 2001 the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) handed down a verdict stating that it had been “proven beyond all reasonable doubt that genocide, crimes against humanity and violations of the laws or customs of war were perpetrated against the Bosnian Muslims, at Srebrenica, in July 1995.”[2]

The trial chamber found that “following the take-over of Srebrenica, Bosnian Serb forces executed several thousand Bosnian Muslim men. The total number is likely to be within the range of 7,000 – 8,000 men.”[3]

In 2010 a second ICTY Trial Chamber was “satisfied beyond reasonable doubt” that as many as 7,826 people “were killed in the executions following the fall of Srebrenica.”[4]

It would appear to be an open and shut case of genocidal Serbs attacking a UN Safe Area and butchering thousands of defenseless Muslim civilians. The journalists, the politicians, and even the courts have certainly made their opinions known, but are those opinions based on reliable evidence or are they politically motivated?

This paper will examine the political significance of the Srebrenica massacre and challenge the widely-held belief that the massacre targeted civilians, that there were nearly 8,000 victims, and that the massacre was an act of genocide.

Nothing in this paper should be construed as denying, condoning, or in any way excusing the Srebrenica massacre. The massacre was undoubtedly a war crime for which the perpetrators should be punished.

Nobody denies that a massacre took place. Slobodan Milosevic described the massacre as an “insane crime”. [5] Radovan Karadzic told the ICTY, “I believe that for thousands of [Srebrenica victims] we can assume that people’s hands were tied, and based on that we can assume that those people were executed.”[6]

The controversy has

to do with numbers killed, the civilian or military status of the victims, and

the underlying motive behind the crime. This paper does not deny that a crime

was committed, but it does argue that the crime has been greatly exaggerated

for political reasons.

The Political Significance of the Srebrenica Massacre

The Srebrenica massacre, and especially it’s classification as genocide, is of tremendous political significance to the political leaders of the Bosnian-Muslims.

The Bosnian-Muslim political leadership has one longstanding goal: to control all of Bosnia, and they aim to do that by wiping Republika Srpska off the map. That was their goal during the war, and it remains their goal today. They hope to accomplish this goal by convincing the world that Republika Srpska should be abolished because it is the product of genocide -- specifically the July 1995 Srebrenica massacre.

Richard Butler, a military expert employed by the ICTY Prosecution, put it bluntly: “The goal of the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina was to establish their control over the entirety of Bosnia and Herzegovina as the military arm of the government in Sarajevo.”[7]

In 1995, former Croatian President Franjo Tudjman informed American officials that Bosnian-Muslim leaders had told him their plan for the Serbs was to “exterminate them all” and to “drive one and a half million Serbs out of Bosnia.”[8]

Even the ICTY Prosecution has noted that “the mere presence and employment in combat of the Mujahedin and EMD during the war in BiH casts serious doubts on the sincerity of the ARBiH’s stated goal of maintaining a secular and multi-ethnic Bosnia where all nationalities could live peacefully.”[9]

The US Central Intelligence Agency had similar doubts about the Sarajevo regime’s commitment to establishing a secular multiethnic state. A recently declassified CIA report authored during the war noted that “the Army’s nominal Deputy Commander, Brigadier General Jovan Divjak, a Serb, acts primarily as the leadership’s token non-Muslim; he reportedly plays only a minimal role in army operations.” According to the report, “The primary Muslim political party-the Party of Democratic Action (SDA) has dominated the Army in almost the same way that the Yugoslav League of Communists dominated the JNA.”[10]

While this information mirrors what many Serbs have been saying all along, it does carry more weight coming from sources that have typically been unsympathetic and even hostile towards the Serbs.

Bosnian-Muslim political leaders have made no secret of the fact that they want to abolish Republika Srpska and that their main argument for doing so is the alleged “genocide in Srebrenica”. Confidential diplomatic cables authored by the U.S. Embassy in Sarajevo and leaked to the website Wikileaks shine a bright light on the Bosnian-Muslim political agenda and their attempts to exploit the so-called “genocide” in Srebrenica.

The cables note, “In February 2007, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) verdict that genocide was committed in and around Srebrenica in July 1995 unleashed pent-up Bosniak anger about the 1992-1995 war. Bosniak political leaders exploited the verdict in order to advance their own narrow, nationalist political agenda.”[11]

Of particular interest to the Americans was the role played by Haris Silajdzic. They reported that he “seized on the ruling as the basis for his claims that the Republika Srpska is an unlawful creation of genocide.”[12]

According to the cables, “Bosniak political leaders, led by Haris Silajdzic, began a strident campaign for ‘special status’ for Srebrenica, essentially calling for its secession from the Republika Srpska (RS). They also encouraged a mass emigration of Bosniak returnees from Srebrenica, claiming conditions there were intolerable.”[13] They quoted Silajdzic as saying, “Srebrenica deserves special status because ‘it was like Auschwitz’ where people were brought to be killed.”[14]

Silajdzic’s arguments were laid out in meticulous detail in the cables. According to him the “issuance of the ICJ verdict had provided a new legal basis from which to retroactively question the terms of Dayton.”[15] He said, Srebrenica is not “just any other” place; “genocide occurred there.” [16]

He said that he was able to accept Srebrenica’s incorporation into the RS at Dayton because there had been no “official determination” in 1995 that genocide took place from July 11, 1995 in Srebrenica. The ICJ changed “the facts on the ground,” and he planned to “exhaust every legal avenue to revise the results of genocide.”[17] According to Silajdzic, “We have to change our structure and our constitution, which were created as the direct result of genocide.”[18]

Silajdzic “stated that Dayton was formed by necessity with pressure from Milosevic, Tudjman and the international community, but the RS cannot remain as is; otherwise it will legalize genocide. ‘We had to sign Dayton with a gun at our heads,’ he said.”[19]

One of the cables noted that “Silajdzic’s goal is clear. He seeks to use the ICJ verdict as a legal basis for the elimination of the Republika Srpska.”[20] Another cable quoted Silajdzic openly declaring that “the RS, a product of genocide, should be abolished, and the moral obligation to implement the ICJ verdict overrules Bosnian law and international treaties, including the Dayton Peace Agreement.”[21]

According to the cables, Silajdzic’s “strategy is aimed at further inflaming Bosniak Muslim opinion here, thereby focusing U.S. and international attention on their grievances. It is unfortunate that few observers in Bosnia itself are able to see through the sophistry of his arguments.”[22] The American officials said, “We are quite frankly concerned with the radical ideas that Silajdzic is successfully sowing here among Bosniaks.”[23]

The cables also expose the exploitation and manipulation of the massacre victims’ surviving family members by the Sarajevo regime.

A cable reporting on a protest against the American ambassador’s visit to the Potocari Memorial staged by the NGO “Mothers of Srebrenica” led by Hatidza Mehmedovic noted that “Bosniak politicians frequently manipulate and exploit the suffering of the mothers of Srebrenica victims, who lack a sophisticated understanding of Bosnia’s criminal justice system let alone international jurisprudence. Though their pain and suffering is real and justified, this ‘spontaneous’ protest was likely orchestrated by others. The mothers do not speak English, and we overheard several asking for translations of their English language signs. In addition, during the protest, a local embassy staff member overheard one of the mothers receiving instructions by phone.”[24]

Another cable noted how “Bosniak political leaders, created a tent settlement of ‘Srebrenica refugees’ in Sarajevo, staged protests outside the Presidency, and even faked an attack on a Bosniak returnee in the village of Ljeskovik to gain public support for Srebrenica’s secession” from Republika Srpska.[25]

The cables pointed out that “High-level visitors to Srebrenica, whether religious or political, come to ‘score points’ and burnish their images as ‘good Bosniaks.’ Local leaders often willingly play in this game.”[26]

Politicians and pundits outside of Bosnia are also keen to exploit the Srebrenica massacre for their own purposes. Whenever military action is being contemplated, you can usually find a politician or a commentator somewhere in the Western news media talking about the need to “prevent another Srebrenica” whether it’s in Iraq, Libya, or Syria. Ironically, it’s usually a Muslim country that they want to attack when they invoke Srebrenica.

The Findings of the ICJ

As alluded to by the American diplomatic cables quoted above, the International Court of Justice issued the following finding in 2007:

“The Court concludes that the acts committed at Srebrenica falling within Article II (a) and (b) of the Convention were committed with the specific intent to destroy in part the group of the Muslims of Bosnia and Herzegovina as such; and accordingly that these were acts of genocide, committed by members of the VRS in and around Srebrenica from about 13 July 1995.”[27]

However, it must be noted that the findings of the ICJ with regard to genocide in Srebrenica are based entirely on the findings of the ICTY. According to the ICJ verdict:

“The Court concludes that it should in principle accept as highly persuasive relevant findings of fact made by the Tribunal at trial, unless of course they have been upset on appeal. For the same reasons, any evaluation by the Tribunal based on the facts as so found for instance about the existence of the required intent, is also entitled to due weight.”[28]

One could certainly question the appropriateness of the ICJ using the ICTY’s verdicts to make findings on issues of state-level responsibility, when the judges and prosecutors at the ICTY have explicitly rejected that idea.

They have gone to great lengths to emphasize that “the Court convicts or acquits the individuals with a first and a last name, and not the collective responsibility of the Serbian people.”[29]

In her opening statement in the Slobodan Milosevic trial, Carla del Ponte made it perfectly clear that “No state or organisation is on trial here today. The indictments do not accuse an entire people of being collectively guilty of the crimes, even the crime of genocide. It may be tempting to generalise when dealing with the conduct of leaders at the highest level, but that is an error that must be avoided. Collective guilt forms no part of the Prosecution case. It is not the law of this Tribunal, and I make it clear that I reject the very notion.”[30]

She repeated the same thing in her opening statement at the Popovic trial. She said, “All accused in this Tribunal are brought before you to be tried for their individual criminal responsibility. No state, no nationality, no organisation is on trial for these crimes. Crimes are committed by individual people, and individual people must be held responsible for their criminal acts. There is no such thing as collective guilt before this Tribunal.”[31]

When Judge Rodrigues handed down the verdict in the Krstic trial he said, “We believe that it is essential to make a distinction between what might be collective responsibility and individual responsibility. The Tribunal has not been established to deal with the possibility of collective responsibility. What is of interest to us in each of the trials which we must hear in this Court is to verify whether the evidence presented before us makes it possible to find an accused guilty. We seek to judge only accused who are individually responsible. We do not wish to judge a people. Yes, in the former Yugoslavia there were attacks against civilian populations. Yes, there were massacres. There was persecution. Yes, some of these crimes were committed by Serbian forces. Still, to paraphrase the words of a great humanist, we consider that to associate this evil with Serbian identity would be an insult to the Serbian people and would betray the concept of civil society. It would be just as monstrous, however, not to attach any name to this evil because that could be an offence to the Serbs.

“In July 1995, General Krstic, individually, you agreed to evil, and this is why today this Trial Chamber convicts you and sentences you to 46 years in prison.”[32]

The ICTY puts individuals on trial, and the ICJ puts states on trial. Defense council at the ICTY defend an individual Accused, they don’t present evidence to defend the State itself. By relying exclusively on the ICTY’s findings, the ICJ abused its discretion and transformed individual responsibility into collective responsibility. This abuse of discretion was why the ICJ’s verdict was of such great significance to Bosnian-Muslim politicians who wish to establish the collective guilt of Republika Srpska.

According to the leaked American diplomatic cables at Wikileaks, “[Sulejman] Tihic claims the [ICJ] verdict mentions the role of police and RS army several times. He added that individuals cannot commit genocide, but you need institutions to carry out preparations and execution of genocide.”[33]

While Tihic’s assertion that individuals can’t commit genocide might sound sensible to a reasonable person, we have to keep in mind that that isn’t the way the ICTY defines genocide, and ultimately it was the ICTY that determined that genocide had been committed. The ICJ didn’t make an independent finding of fact, it merely referenced the ICTY’s findings in its verdict, and according to the ICTY lone individuals can commit genocide.

The Trial Chamber in the Jelisic case held that “The murders committed by the accused are sufficient to establish the material element of the crime of genocide and it is a priori possible to conceive that the accused harboured the plan to exterminate an entire group without this intent having been supported by any organisation in which other individuals participated. In this respect, the preparatory work of the Convention of 1948 brings out that premeditation was not selected as a legal ingredient of the crime of genocide, after having been mentioned by the ad hoc committee at the draft stage, on the grounds that it seemed superfluous given the special intention already required by the text and that such precision would only make the burden of proof even greater. It ensues from this omission that the drafters of the Convention did not deem the existence of an organisation or a system serving a genocidal objective as a legal ingredient of the crime. In so doing, they did not discount the possibility of a lone individual seeking to destroy a group as such.”[34]

Computer software engineers have a saying that they like to use: “Garbage in, garbage out”. The saying refers to the fact that computers will unquestioningly process erroneous input data (“garbage in”) to produce erroneous output (“garbage out”).

The same reasoning applies here. Because the ICJ relied exclusively on the findings of the ICTY, the findings of the ICJ are only as reliable as the underlying findings of the ICTY. If the ICTY’s findings are wrong, then the ICJ’s findings are wrong. For that reason, this paper will not devote any further attention to the findings of the ICJ. Instead we will focus on the underlying findings and evidence of the ICTY.

The Military Status of the Missing and Dead

The victims of the Srebrenica massacre are frequently alleged to be innocent unarmed civilians. Gareth Evans and James Lyon, the president and senior Balkan analyst of the International Crisis Group, informed readers of the International Herald Tribune that “In mid-July 1995, Bosnian Serb forces commanded by Mladic conducted the organized slaughter of nearly 8,000 civilians and non-combatants around the Bosnian town of Srebrenica.”[35]

The London Mirror carried a similar report on the “murder of 8,000 civilians at Srebrenica during the Bosnian war.” They assured their readers that “the victims – unarmed Muslim men and boys – were butchered by Serb forces after they captured the small town of Srebrenica in 1995.”[36]

In the United States, the White House issued a statement in 2005 which said, “On July 11th, we remember the tragic loss of lives in Srebrenica 10 years ago. The mass murder of nearly 8,000 men and boys was Europe’s worst massacre of civilians since World War II, and a grim reminder that there are evil people who will kill the innocent without conscience or mercy.”[37]

According to the UNHCR, “Nearly 8,000 civilians were slaughtered in the worst atrocity in Europe since World War II. The International War Crimes Tribunal in The Hague … judged the action as genocide.”[38]

An in-depth discussion about the number of victims will come later, but for right now let’s deal with the allegation that these “men and boys” were civilians, and not soldiers in the Bosnian-Muslim army.

Although one could certainly speculate that the intent was to vilify the Serbs or to inflame public opinion for political reasons, this paper will not attempt to explain what possessed the entire Western news media and political establishment to make these allegations. Instead, the allegations will be held against the evidence adduced at the ICTY so that the reader may observe for himself how far detached from reality they are.

Although a number of civilians were certainly killed, the evidence strongly suggests that the vast majority of missing persons and confirmed deaths were soldiers and military aged men. The Krstic trial chamber even conceded that “only the men of military age were systematically massacred.”[39]

The ICTY Prosecutor’s own military expert testified that “people who didn’t qualify as military combatants or potential military combatants were not part of that plan [to execute the prisoners]. One of the unique things that I can use that helps me to support that theory is witness testimony that was brought before the Court earlier where on 13 July in the Sandici meadow, there was an awareness that they were looking to exclude out of the groups of people individuals who were not between the ages of 16 and 60. And that was an awareness by the soldiers at the lowest level.”[40]

In 2005 the Office of the Prosecutor at the ICTY compiled a list of 7,661 persons (military and civilian) who went missing or were confirmed dead after Srebrenica fell to Bosnian-Serb forces in July of 1995.[41]

6,847 out of the 7,661 people on the list were men between the ages of 16 and 60.[42] This is significant because a military draft was in effect in Srebrenica. The order for general mobilization issued by the Srebrenica War Presidency called for the immediate mobilization of “all able-bodied citizens aged between 16 and 60 years of age.”[43]

Moreover, the demographic unit of the ICTY Prosecutor’s office found ABiH military service records for 5,371 of the 7,661 people on the list of Srebrenica’s missing and dead.[44]

The allegation that the massacre victims were primarily civilians doesn’t hold in the face of evidence on record at the ICTY, most of it tendered by the Prosecution itself, showing that the overwhelming majority of Srebrenica’s missing and dead were military aged men with accompanying military service records.

Genocide

As already noted, the Srebrenica massacre’s classification as an act of “genocide” by the ICTY is of major political importance to the political leadership of the Bosnian-Muslims in their ongoing quest to abolish Republika Srpska.

In order to determine whether the evidence supports a finding of genocide, one must first understand what genocide is, and what it isn’t.

Article 2 of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide defines genocide as follows:

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a)

Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring

about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

The ICTY appeals chamber has determined that “As a specific intent offense, the crime of genocide requires proof of intent to commit the underlying act and proof of intent to destroy the targeted group, in whole or in part.”[45]

The Popovic trial chamber further elaborated, “What distinguishes genocide is genocidal intent – the ‘intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such’ … The words ‘as such’ underscore that something more than discriminatory intent is required for genocide; there must be intent to destroy, in whole or in part, the protected group.”[46]

The Krstic trial chamber noted that “The victims of genocide must be targeted by reason of their membership in a group. This is the only interpretation coinciding with the intent which characterizes the crime of genocide. The intent to destroy a group as such, in whole or in part, presupposes that the victims were chosen by reason of their membership in the group whose destruction was sought. Mere knowledge of the victims’ membership in a distinct group on the part of the perpetrators is not sufficient to establish an intention to destroy the group as such.”[47]

The Krstic trial chamber further noted that “the Genocide Convention does not protect all types of human groups. Its application is confined to national, ethnical, racial or religious groups.”[48]

In order to accurately classify the Srebrenica massacre as an act of genocide it must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt that the victims, who were mainly soldiers and military aged men, were killed with the specific intent to destroy the Bosnian-Muslim ethno-religious group as such, and not because they were combatants or potential military combatants engaged in a war against the Bosnian-Serbs.

Although the Tribunal correctly defines genocide, the evidentiary threshold required to prove it is ridiculously low. According to the Tribunal, “The existence of a plan or policy is not a legal ingredient of the crime of genocide.”[49] They have also found that “The perpetrator’s genocidal intent will almost invariably encompass civilians, but that is not a legal requirement of the offence of genocide.”[50] The Appeals Chamber in the Karadzic case held that “The determination of whether there is evidence capable of supporting a conviction for genocide does not involve a numerical assessment of the number of people killed and does not have a numeric threshold.”[51]

The bar is set so low that any armed conflict could be classified as genocide. A genocide conviction under these circumstances is practically meaningless. The Prosecutor doesn’t have to prove that there was a genocidal plan, he doesn’t have to show how many people were killed, or even that the victims were civilians.

The Krstic defense argued before the ICTY Appeals chamber that his genocide conviction should be overturned because “the record contains no statements by members of the VRS Main Staff indicating that the killing of the Bosnian Muslim men was motivated by genocidal intent to destroy the Bosnian Muslims of Srebrenica.” Without disputing the factual claim, the Tribunal dismissed the argument on the grounds that “The absence of such statements is not determinative. Where direct evidence of genocidal intent is absent, the intent may still be inferred from the factual circumstances of the crime.”[52]

In criminal law there are two types of evidence, direct evidence and circumstantial evidence. The ICTY’s findings with regard to genocide at Srebrenica are based entirely on circumstantial evidence.

The Popovic trial chamber noted that “by its nature, [genocidal] intent is not usually susceptible to direct proof’ because ‘[o]nly the accused himself has first-hand knowledge of his own mental state, and he is unlikely to testify to his own genocidal intent.’ Absent direct evidence, the intent to destroy may be inferred [from other facts and circumstances].”[53] They even cautioned that “Where an inference is drawn from circumstantial evidence to establish a fact on which a conviction relies, that inference must be the only reasonable one that could be drawn from the evidence presented.”[54]

The question here is whether genocidal intent to destroy the Bosnian-Muslim ethno-religious group as such is a reasonable inference, let alone the only reasonable inference, that can be drawn from the killing of enemy soldiers and military aged men in the midst of an ongoing war.

The Krstic appeals judgment states that “The main evidence underlying the Trial Chamber’s conclusion that the VRS forces intended to eliminate all the Bosnian Muslims of Srebrenica was the massacre by the VRS of all men of military age from that community … The killing of the military aged men was, assuredly, a physical destruction, and given the scope of the killings the Trial Chamber could legitimately draw the inference that their extermination was motivated by a genocidal intent.”[55]

The reasoning employed by the Popovic Trial chamber is almost identical. They held that “It is clear from the evidence that the Bosnian Serb Forces intended to kill Bosnian Muslim able-bodied males from Srebrenica on a massive scale … The Trial Chamber finds that the killing of all of the male members of a population is a sufficient basis to infer the intent to biologically destroy the entire group.”[56]

The Krstic trial chamber cited the fact that “Only the men of military age were systematically massacred” and that “their death precluded any effective attempt by the Bosnian Muslims to recapture the territory”[57] to support their dubious conclusion “that the intent to kill all the Bosnian Muslim men of military age in Srebrenica constitutes an intent to destroy in part the Bosnian Muslim group.”[58]

Killing military aged men to prevent them from recapturing territory is plainly not the same thing as killing people to destroy their ethnic group. The mental gymnastics that the Tribunal employs to prop-up these allegations of “genocide” would be laughable if the allegations weren’t so grave.

If the Bosnian-Serb Army’s goal was to destroy the Bosnian-Muslim ethnic group as such, then why didn’t it kill the women and children along with the military aged men?

The Tribunal has an answer. They say, “The decision not to kill the women or children may be explained by the Bosnian Serbs’ sensitivity to public opinion. In contrast to the killing of the captured military men, such an action could not easily be kept secret, or disguised as a military operation, and so carried an increased risk of attracting international censure.”[59]

Krstic trial chamber’s position that “The intent to destroy a group as such, in whole or in part, presupposes that the victims were chosen by reason of their membership in the group whose destruction was sought” should be recalled.[60] Does the Tribunal’s explanation for why the women and children weren’t killed sound like proof beyond a reasonable doubt, or does it sound like speculation that attempts to justify a finding of genocidal intent that isn’t supported by the evidence?

The Tribunal does its best to rule out a military motive for the massacre. The Krstic trial chamber asserted that “The VRS may have initially considered only targeting the military men for execution. Some men from the column were in fact killed in combat and it is not certain that the VRS intended at first to kill all the captured Muslim men, including the civilians in the column. Evidence shows, however, that a decision was taken, at some point, to capture and kill all the Bosnian Muslim men indiscriminately. No effort thereafter was made to distinguish the soldiers from the civilians. Identification papers and personal belongings were taken away from both Bosnian Muslim men at Potocari and from men captured from the column; their papers and belongings were piled up and eventually burnt.”[61]

The Popovic Trial Chamber cited evidence that the prisoners “were not asked to give their names, nor were they interviewed by anyone”[62] and that “the members of the Bosnian Serb Forces did not seem to have a list with the names of the prisoners, and at no point during that night [at one of the execution sites] did they ask the prisoners for their names.”[63]

The argument that the Tribunal is attempting to advance is that if the Serbs didn’t check the identity of the prisoners, they couldn’t have known who was a soldier and who was a civilian. Therefore, the military couldn’t have been the target.

That’s fallacious reasoning because it was common knowledge that a military draft was in effect, and so the Serbs would have known that all of the men between the ages of 16 and 60 were supposed to be in the military.

The Tribunal’s reasoning is a double edged sword. If one accepts that line of reasoning as credible, then one must reject the idea that the Bosnian-Serb Army had genocidal intent. Although one can estimate whether a man is between the age of 16 and 60 by his appearance, one cannot tell the difference between a Muslim, a Serb, or a Croat by their appearance. If the Serbs weren’t checking IDs, then how could they know if their prisoners were Bosnian-Muslims or not? If they didn’t know the ethnicity of the prisoners, then how could they possibly target the Bosnian-Muslim ethno-religious group for destruction?

The Serbs weren’t stupid. They knew that Srebrenica was populated by Bosnian-Muslims and they knew that the men between the ages of 16 and 60 had been drafted. One has to approach this subject with at least some measure of common sense and the Tribunal isn’t.

It is an undisputed fact that 6,847 out of the 7,661 people on the Prosecution’s list of missing and dead were military aged men between the ages of 16 and 60.[64] It is also an undisputed fact that military records have been found for 5,371 of them.[65] It is clear, therefore, that the soldiers and the military aged men were the intended target of the massacre.

The Popovic trial chamber has noted that “some young boys, elderly men and the infirm were amongst those killed”[66] and the Krstic trial chamber has noted that “some of the victims were severely handicapped and, for that reason, unlikely to have been combatants.”[67] Nobody denies that those are the facts, but when nearly 90% of the missing and dead are military aged men and most of them have accompanying military records it is impossible to accept Tribunal’s conclusion “that no distinction was made between civilians and military men”.[68] Obviously a distinction of some sort was made, otherwise 90% of the missing and dead wouldn’t have been soldiers or military aged men.

Plainly, the

intended target of the massacre was the opposing military and not the

Bosnian-Muslim ethno-religious group as such. Therefore the massacre, although

still a war crime, was not an act of genocide.

The ICTY’s Credibility

It would appear that the ICTY’s findings, particularly with regard to genocide at Srebrenica, are not based upon reliable evidence. In fact, the US diplomatic cables leaked to Wikileaks contain smoking gun evidence that destroys the ICTY’s credibility.

When the ICTY Appeals Chamber handed down its verdict in the Radislav Krstic trial, American embassy personnel in The Hague reported back to Washington that “There is a general sense among prosecutors that the Appeals Chamber first decided that Krstic did not merit conviction as a principal perpetrator of genocide but that, for ‘political’ reasons, it did not want to set aside the finding that the massacres around Srebrenica constituted genocide. The result, one prosecutor said, made it seem as if ‘an eighteen year-old law clerk’ had written the judgment on the basis of a decision reached ‘by academics and diplomats’. In fact, a law clerk involved in the drafting confirmed to embassy legal officers that the chamber had given the drafters general directions, ‘the bottom line,’ and that the law clerk drafters had to determine how to get there.”[69]

Rather than the evidence leading them to their conclusion, the law clerks who wrote the Krstic appeals judgment were presented with a politically motivated conclusion ahead of time and their job was to “determine how to get there”.

Judge Frederik Harhoff was removed from the Tribunal’s bench after he circulated a letter accusing the President of the ICTY of exerting pressure on his fellow judges in their deliberations because of “pressure from ‘the military establishments’ in certain dominant countries” -- particularly the United States.[70]

Another American diplomatic cable dating from 2007 shows that France wanted the job of ICTY Chief Prosecutor to be given to Serge Brammertz for blatantly political reasons.

According to the cable, “France is backing Serge Brammertz to succeed Carla Del Ponte as ICTY Chief Prosecutor from a belief that Brammertz will otherwise refuse to extend his mandate at the UN International Investigative Commission (UNIIIC), an outcome the French characterize as disastrous. MFA UN/Middle East Action Officer Salina Grenet explained to Poloff on May 10 that Brammertz was conditioning any prolongation of his UNIIIC duties on a guarantee -- by June 15 at the latest -- of a suitable onward assignment.”[71]

The apparent fact that the ICTY’s chief prosecutor got his job for political reasons is particularly significant because it is the Prosecution that decides who gets accused of genocide and who doesn’t. The Prosecution writes up the indictment, but the Defense can only present evidence that is relevant to the indictment. This gives the prosecution an almost limitless power to suppress evidence of war crimes and pervert the historical record.

In the Karadzic trial, the presiding judge admitted in open court that “We didn’t allow the accused to expand on the issue of crimes committed against the Serbs.”[72] The same trial chamber also ruled that “the issue of who was responsible for starting the war is not relevant to the Accused’s defence case” when it denied his request to subpoena documents from the American government.[73]

As previously noted, genocide is an intent specific crime. The issue of crimes against Serbs and the issue of who started the war determines the context in which the massacre was committed. Without an understanding of the context in which it occurred, one cannot understand the mindset of the Bosnian Serbs, or make an intelligent determination as to whether the massacre was motivated by genocidal intent or not.

Moreover, if a defendant like Radovan Karadzic is not allowed to present evidence of war crimes against Serbs, then we have to rely on the Prosecution to do that and to bring the perpetrators to justice.

Unfortunately, there is evidence that Serbs have been targeted for selective prosecution by the ICTY. In 2006 a survey of twenty-five forensic pathologists employed by the Tribunal was conducted, and the results were published in the prestigious academic journal “Medicine, Science and the Law.”[74]

The study found that “some of the forensic pathologists involved belonged to human rights organizations that were not neutral in the conflicts. Moreover, most of them belonged to countries which are NATO members.”

In spite of the Tribunal’s attempt to stack the deck with pathologists that would be sympathetic to the NATO cause, the study found that of the twenty-five pathologists surveyed: “Three forensic pathologists reported that they had been subjected to pressures, one by the Croatian government, the two others by a human rights organization, a non-governmental organization which controlled the course of autopsies and also concerning the writing of the autopsy reports.”

Moreover, “Three forensic pathologists were aware of mass grave sites wittingly not investigated by the ICTY, especially mass graves of Serbian victims” and “four of them questioned the impartiality of the justice led by the ICTY.”

The study noted disturbing irregularities concerning the ICTY’s forensic investigations, including that the “financial independence of the forensic pathologists could be questioned as not all of them have been paid directly by the ICTY according to the comments of some of our respondents.”

The study also noted what it called a “disturbing feature of the ICTY proceedings” where “not all forensic pathologists involved presented verbal evidence to the court in The Hague, but only the senior chief forensic pathologist of the team appeared to give evidence, in contradiction to the tradition that the responsibilities of an individual forensic scientist are personal and not corporate.”

The selective nature of the ICTY’s prosecutions are obvious. Serbs are prosecuted while their opponents are given impunity for exactly the same offenses.

For example, Milan Martic was indicted by the ICTY for using cluster bombs against Zagreb in retaliation for Operation Flash. According to the indictment, the cluster bomb attacks killed seven people.[75]

On May 7, 1999 NATO warplanes dropped cluster bombs on the Serbian city of Nis. The bombs hit a hospital and a market killing 15 civilians.[76] Yet nobody from NATO was brought up on war crimes charges by the ICTY. Obviously, if it’s a war crime to drop cluster bombs on Zagreb, then it’s a war crime to drop cluster bombs on Nis.

The double standard is plain to see. The ICTY prosecuted Dragomir Milosevic for shelling the TV Sarajevo building. According to the indictment, the attack left one person dead and 28 wounded.[77]

On April 23, 1999 NATO bombed Radio Television Serbia’s main studio in Belgrade. According to the BBC the attack killed 10 people and left another 18 wounded.[78] Nobody from NATO was prosecuted by the ICTY. Again, if it’s a war crime to bomb a TV station in Sarajevo, then it’s a war crime to bomb a TV station in Belgrade.

Gen. Milosevic was also prosecuted for firing on buses and trams in Sarajevo. The indictment listed 10 people killed as a result of these attacks.[79] But when NATO bombed a commuter train near Grdelica on April 12, 1999 killing 9 civilians,[80] and a bus in Luzane on May 3, 1999 killing another 23 civilians,[81] there wasn’t a peep out of the ICTY prosecutor. Yet again, if it’s a war crime to fire on busses and trams in Bosnia, then surely it’s a war crime to bomb busses and commuter trains in Serbia. The Prosecution at the ICTY is obviously selective.

Richard Goldstone was the ICTY’s first chief prosecutor, and he recently stated the obvious in the San Francisco Chronicle. He told them point blank that “international criminal justice (is) all about politics.”[82]

The Tribunal is the brainchild of the CIA. Documents recently declassified by the Clinton Presidential Library show that the Tribunal began as a U.S. policy initiative. On 1 February 1993, the Director of the CIA circulated a memo that assessed how various countries would respond to “US policy options” in the former Yugoslavia.

One of the policy options was to “establish a war crimes tribunal”. According to the memo, Western Europeans would be supportive of the Tribunal, Moscow would oppose it, and “Muslim states would approve a War Crimes Tribunal and publicizing Serbian atrocities. Even treatment of Bosnian transgressions, however, would be regarded as tilting in Belgrade’s favor.”[83]

It was the United States that pushed hardest for the Tribunal. In a speech at the U.S. Supreme Court, former ICTY President Gabrielle Kirk McDonald was generous in her praise for former US Secretary of State Madeline Albright. She said, “We benefited from the strong support of concerned governments and dedicated individuals such as Secretary Albright. As the permanent representative to the United Nations, she had worked with unceasing resolve to establish the Tribunal. Indeed, we often refer to her as the ‘mother of the Tribunal’.”[84]

The ICTY has been used for political purposes since its inception. In an interview with BBC Radio, former U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Richard Holbrooke said, “When President Clinton brought me back to Washington to take over the Bosnia negotiations I realized that the War Crimes Tribunal was a huge valuable tool. We used it to keep the two most wanted war criminals in Europe - Karadzic and Mladic - out of the Dayton peace process and we used it to justify everything that followed.”[85]

Former NATO spokesman Jamie Shea openly bragged to the media that “NATO countries are those that have provided the finance to set up the Tribunal, we are amongst the majority financiers.” According to Shea, “Without NATO countries, there would be no International Court of Justice nor would there be any International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, because NATO countries are in the forefront of those who have established these two tribunals, who fund these tribunals, and who support on a daily basis, their activities.”[86]

The possibility of the Tribunal indicting NATO pilots for war crimes was never realistic. The CIA and the State Dept. didn’t set-up the Tribunal to meet out evenhanded justice. That isn’t what NATO pays the Tribunal to do. The real purpose of the Tribunal has always been to justify American and NATO policy in the region – and NATO’s policy was to bomb the Serbs.

When reporters asked Lester Munson, Communications Director for the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on International Relations, if the Tribunal could prosecute NATO officers for attacking civilian targets in Serbia he told them: “You’re more likely to see the UN building dismantled brick-by-brick and thrown into the Atlantic than to see NATO pilots go before a UN tribunal.”[87]

What does this have to do with the Srebrencia massacre? It’s relevant because the ICJ and various politicians, researchers, journalists, and academics have uncritically accepted the ICTY’s findings as credible when they plainly should not have done so.

The ICTY is primarily funded by one of the parties to the conflict (NATO) and it engages in the selective prosecution of Serbs while giving NATO impunity for exactly the same offenses. The ICTY is not impartial and so its findings cannot be taken on faith. By extension any academic research, journalism, or political discourse that relies directly or indirectly on the ICTY’s findings has been compromised as well.

The evidence

that has been presented at the ICTY is of tremendous value, and it will help us

establish what happened at Srebrenica in July 1995, but the findings and

conclusions reached by the Tribunal itself are of no value whatsoever.

Nasir Oric and the 28th Infantry Division

When Nasir Oric, the commander of the 28th Infantry Division of the ARBiH in Srebrenica, was acquitted by the ICTY Appeals Chamber for crimes committed against Serbs, the Head of the ICTY Prosecutor’s Liaison Office, Deyan Mihov, told American Embassy personnel in Belgrade that “It is becoming increasingly obvious that decisions in the chamber are being politically driven.”[88]

What is also obvious is that the Prosecution didn’t really want to convict Oric. Several high profile witnesses who could have testified to his acts and conduct were conspicuously not called to give evidence against him during his trial.

Oric showed videotaped evidence of his handiwork to at least two Western journalists who published reports of what they had seen in major Western newspapers.

John Pomfret reported in the Washington Post that “Nasir Oric’s war trophies don’t line the wall of his comfortable apartment -- one of the few with electricity in this besieged Muslim enclave stuck in the forbidding mountains of eastern Bosnia. They’re on a videocassette tape: burned Serb houses and headless Serb men, their bodies crumpled in a pathetic heap.

“‘We had to use cold weapons that night,’ Oric explains as scenes of dead men sliced by knives roll over his 21-inch Sony. ‘This is the house of a Serb named Ratso,’ he offers as the camera cuts to a burned-out ruin. ‘He killed two of my men, so we torched it. Tough luck.’”[89]

The second journalist was Bill Schiller. He reported on the front page of the Toronto Star that “Oric is a fearsome man, and proud of it.

“I met him in January, 1994, in his own home in Serb-surrounded Srebrenica.

“On a cold and snowy night, I sat in his living room watching a shocking video version of what might have been called Nasir Oric’s Greatest Hits.

“There were burning houses, dead bodies, severed heads, and people fleeing.

“Oric grinned throughout, admiring his handiwork.

“‘We ambushed them,’ he said when a number of dead Serbs appeared on the screen.

“The next sequence of dead bodies had been done in by explosives: ‘We launched those guys to the moon,’ he boasted.

When footage of a bullet-marked ghost town appeared without any visible bodies, Oric hastened to announce: ‘We killed 114 Serbs there.’”[90]

Here you have two Western journalists, an American and a Canadian, who were both shown videotaped evidence of Serbs literally being butchered, cut up with knives, and beheaded by Nasir Oric’s men while Oric himself was smiling and bragging about what he had done, and the prosecutor didn’t put either of them on the witness stand. What does that tell you?

It wouldn’t have been unusual at all for the Prosecution to call journalists to testify. The Prosecution frequently puts journalists on the witness stand. For example, Jeremy Bowen of the BBC has been called to testify in four different trials, Ed Vulliamy of the Guardian has testified for the Prosecution in five trials, Aernout van Lynden of Sky News has testified in seven different trials, and Martin Bell of the BBC has been put on the stand by the Prosecution in five separate trials.

Another high profile witness that the Prosecution didn’t call was Gen. Philippe Morillon of France who served as the Commander of the UN Forces in Bosnia during part of the war. Although the Prosecution did not call Morillon to testify in the Oric trial, they did call him to testify in the Slobodan Milosevic trial where Milosevic questioned him about his dealings with Oric.

Morillon told the Milosevic trial chamber that Oric was “a warlord who reigned by terror in his area and over the population itself”. He said that Oric and his men, “engaged in attacks during Orthodox holidays and destroyed villages, massacring all the inhabitants.”[91] According to Morillon’s witness statement, Oric “admitted to killing Bosnian Serbs each night.”[92]

When asked what Oric did to the Serbs he captured, Morillon explained that “He didn’t even look for an excuse. It was simply a statement: One can’t be bothered with prisoners.” He said, “I wasn’t surprised when the Serbs took me to a village to show me the evacuation of the bodies of the inhabitants that had been thrown into a hole, a village close to Bratunac.”[93]

The Prosecution was obviously not making a good faith effort expose Oric’s crimes and bring him to justice. It looks like the real purpose of Nasic Oric’s trial was to whitewash his crimes and cover them up by deliberately presenting a weak case that would end with his acquittal.

Gen. Morillon let the cat out of the bag when he testified. The Presiding judge in the Milosevic trial asked him point blank, “Are you saying, then, General, that what happened in 1995 was a direct reaction to what Naser Oric did to the Serbs two years before?” and he answered “Yes. Yes, Your Honour. I am convinced of that. This doesn’t mean to pardon or diminish the responsibility of the people who committed that crime, but I am convinced of that, yes.”[94]

Given Gen. Morillon’s testimony about what Nasir Oric and the men under his command did to the Serbs in the area, it isn’t hard to understand why the Serbs might have harbored some resentment against the Muslim soldiers and military aged men that were trying to break out of Srebrenica.

Zvonko Bajagic summed-up the Serbian view of the situation when he testified in the Radovan Karadzic trial. He described the Muslim prisoners from Srebrenica that he saw being held captive saying, “I was not in the least interested in them, because they were soldiers, and they were the cause of a lot of plight and sorrow. They killed a lot of Serbs. They plundered and burned villages. Maybe not all of them, but in my eyes they were all villains and criminals. It was supposed to be a demilitarised zone, and they were armed to the teeth. They had more ammunition than we did. Whenever they wanted they entered our territory, and whenever they did that they committed crimes. They killed people. They plundered and burned. In the village of Podravanje, they took one of my own employees, they impaled him and they grilled him on the spit.”[95]

The fact that Srebrenica had been declared a UN Safe Area didn’t stop the Muslims from launching attacks out of the enclave.

Just two weeks before the Bosnian Serb Army attacked Srebrenica, the Muslims attacked a small, undefended Serbian village. At 4:30 AM on June 26, 1995, Muslim forces from Srebrenica attacked the Serb village of Visnjica, burning houses, killing livestock, and forcing the civilian population to flee for their lives.[96]

Gen. Morillon described the mindset of the Serbs in the area. He said, “the local Serbs, the Serbs of Bratunac, these militiamen, they wanted to take their revenge for everything that they attributed to Naser Oric. It wasn’t just Naser Oric that they wanted to revenge, take their revenge on, they wanted to revenge their dead on Orthodox Christmas. They were in this hellish circle of revenge. It was more than revenge that animated them all.

“Not only the men. The women, the entire population was imbued with this. It wasn’t the sickness of fear that had infected the entire population of Bosnia-Herzegovina, the fear of being dominated, of being eliminated, it was pure hatred.”[97]

The Attack on Srebrenica

On July 2, 1995 Major-General Milenko Zivanovic issued the Drina Corps of the Bosnian-Serb Army (VRS) an order to “Split apart the enclaves of Zepa and Srebrenica and to reduce them to their urban areas.” The order explained that “During the last few days, Muslim forces from the enclaves of Zepa and Srebrenica have been particularly active. They are infiltrating sabotage groups which are attacking and burning undefended villages, killing civilians, and small isolated units around the enclaves of Zepa and Srebrenica. They are trying extremely hard to link up the enclaves and open a corridor to Kladanj.”[98]

The operation, codenamed “Krivaja 95” was launched on the 6th of July. Col. Thomas Karremans was the commander of the UN Dutch Battalion that was stationed in Srebrenica at the time. He testified that “On the 6th of July, in the morning, about 3:00, the war started over there. It started in our area, the compound of Potocari, by shooting over the compound with some rockets. The attacks started in the southern part of the enclave, in the area of OP Foxtrot. That was on the Thursday, Thursday, the 6th of July, and those attacks were carried out, let’s say, during six days.”[99]

Late on 9 July 1995, Bosnian-Serb President Radovan Karadzic issued an additional order, expanding the scope of the original Krivaja 95 orders, and authorizing the VRS to take over the entire Srebrenica enclave.[100]

The Formation of the Column

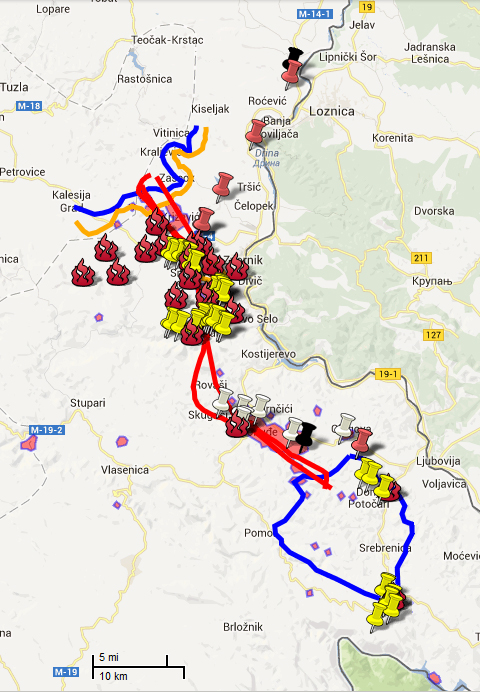

On the evening of 10 July, word spread through Srebrenica that the enclave was about to fall and that able-bodied men should take to the woods and form a column together with members of the 28th Division of the ABiH and attempt a breakthrough towards Bosnian Muslim-held territory near Tuzla.[101]

According to the ABiH’s own internal reporting, “On the night of 11/12 July 1995, the decision was taken to break through towards Tuzla … The commanders were ordered to line up the units and form a column.”

According to their report, “Numbers were not established when the column was formed and set off that evening, but some estimates put the number in the column at 10,000 to 15,000 people, including approximately 6,000 armed soldiers, not counting soldiers from Zepa. There were not many women and children in the column. There were possibly around 10 women.”[102]

While the army and the able-bodied men were forming the column to break-through the Bosnian-Serb lines and reach Tuzla, approximately 25,000 civilians gathered around the UN compound in Potocari.

The Separation of Men at Potocari

According to Col. Karremans, “Of those 25,000 refugees, most of them were women, children, and elderly people. There were about two to three per cent men between 16 and 60.”[103] His deputy Robert Franken estimated that “there were about 300, 350 men within the compound, and we estimated that there were 500 to 600 men outside the compound. The rest were women and children.”[104]

When Bosnian-Serb forces entered Potocari on July 12th they separated the men from the rest of the refugees and held them prisoner. The women, children and elderly were loaded onto buses and sent to Muslim-held territory in Kladanj.

According to Franken, “One of the demands or rules Mladic gave us was -- or his intents, he told us that he intended to separate the men between 16 and 60 years to check whether they were war criminals or soldiers.”[105]

He explained that separating the men to determine who was a combatant and who was a civilian was “in those days, a normal procedure” because it was difficult to distinguish who was a combatant in an environment where the soldiers didn’t always wear their uniforms.[106]

1,487 of the men on the ICTY Prosecutor’s list of Srebrenica missing and dead were last seen by their families in Potocari on July 12-13.[107] Prosecutors and the judges at the ICTY estimate that the number of men taken prisoner by Bosnian Serb forces at Potocari was about 1,000.[108] This is roughly consistent with upper end of Karremans and Franken’s estimate of the number of men that were present among the refugees.

Men Captured From the Column

In addition to the men separated at Potocari, Bosnian-Serb forces also captured prisoners from the column of Muslim men that broke out of the enclave.

The vast majority of men captured from the column were captured on July 12th and 13th as they attempted to cross the Bratunac – Konjevic Polje – Milici Road. These prisoners were detained at two main sites: the Sandici meadow and a football field in Nova Kasaba.

Smaller groups were captured at Konjevic Polje, Jadar River, Luke School, and in the general area around Burnice, Sandici, Kamenica, Krajinovici and Mratinci all the way until the 17th of July.

According to the ICTY prosecution: On the evening of July 13th two busloads of prisoners held at an agricultural warehouse in Konjevic Polje were sent to Bratunac.[109] The busses were not completely full and stopped to pick up prisoners at Sandici Meadow on their way.[110] On the morning of July 13th sixteen men were captured by Bosnian-Serb forces and taken to a remote part of the Jadar River where they were killed on the spot.[111] On July 13th, six Bosnian Muslim men were captured, and then interrogated and killed at the Bratunac brigade headquarters.[112] Between July 13th and 17th 200 prisoners were captured in a sweep of the terrain between Sandici, Kamenica, Krajinovici and Mratinci towards Konjevic Polje.[113] On July 13th at Luke School near Tisca 22 men were captured off of busses transporting refugees and killed.[114]

By my reckoning, the ICTY prosecution claims to have adduced evidence showing that the number of prisoners captured and detained at places other than Potocari, Nova Kasaba, and Sandici meadow was about 350 to 400 prisoners.

The men taken prisoner in Potocari and the men captured from the column over the course of July 12-13 were sent to Bratunac, and on the morning of July 14 they were sent north to the Zvornik municipality where they were killed. Except for part of the prisoners on Sandici Meadow who were sent to a warehouse in Krivica and killed there on the evening of July 13th.

Prisoners at Nova Kasaba

According to the ICTY, “1,500 to 3,000 men captured from the column were held prisoner on the Nova Kasaba football field on 13 July 1995.”[115] The Krstic trial chamber based this finding on the testimony of two of the prisoners who were held captive on the field: “Witness P” and “Witness Q.”

However, better evidence exists than what was relied upon by the Tribunal. The best evidence is an aerial reconnaissance photograph that was produced by the United States showing the group of prisoners sitting on the Nova Kasaba football field on the afternoon of July 13th.

According to the CIA’s estimation, there are approximately 600 prisoners visible in this photograph.[116]

The CIA’s estimate can be corroborated by overlaying the reconnaissance photograph in Google Earth and measuring how much ground space is occupied by the prisoners. These measurements show that the prisoners occupied about 670 square meters of ground space.[117]

It is important to note that this picture was taken at about 2:00 PM in the afternoon, while the process of capturing the prisoners was still underway and so prisoners continued to arrive after it was taken.

Zoran Malinic was a Bosnian-Serb soldier tasked with guarding and compiling a list of prisoners and he testified in the Tolimir trial that the prisoners were held there until about 6:00 PM on July 13th when they were loaded on busses and sent to Bratunac. He estimated the total number of prisoners held captive at Nova Kasaba to be between 1,000 and 1,200.[118]

Bojan Subotic, commander of the Bosnian-Serb military police platoon tasked with loading the prisoners onto the busses and trucks, testified that at around 7 p.m. on 13 July, about fifteen vehicles arrived at the Nova Kasaba Football Field to transport the prisoners to Bratunac.[119] If we assume that about 70 people were loaded onto each vehicle that gives us about 1,050 prisoners.

Based on this evidence, we can be reasonably certain that sometime around 6:00 or 7:00 on the evening of July 13th approximately 1,100 prisoners were loaded on to buses and trucks and sent from the Nova Kasaba football field to Bratunac.

This would mean that approximately 500 prisoners arrived at the football field in the four or five hours after the reconnaissance picture was taken.

The process of capturing prisoners and bringing them to the football field had been underway since the day before.

Lt. Vincentius Egbers, was a soldier in the Royal Dutch Army who was deployed to the Srebrenica enclave with DutchBat III. On July 12th he saw “between 100 and 200 men” lined up on the field “sitting on their knees with their hands in their neck.”[120] On July 13th he passed by the field again in the morning and saw “there were still men on the football field and men who were brought towards the football field at the day before” he estimated their number to be “a few hundred”.[121]

It is difficult to believe that in only 4 or 5 hours after the picture was taken that the number of prisoners skyrocketed from the 600 who were photographed at 2:00 PM to 3,000 as alleged by the Tribunal. The estimates of Malinic and Subotic that place the total number of prisoners at approximately 1,100 seem the most credible.

Prisoners at Sandici Meadow

Throughout the morning and afternoon of July 13th Bosnian-Muslim men from the column surrendered to, or were captured by, Bosnian-Serb troops at Sandici meadow. Some of the prisoners were sent to Kravica warehouse 1.2 kilometers away and massacred there at approximately 5:00 PM that evening. The rest of the prisoners remained on the meadow before being sent to Bratunac later that day.

The Popovic trial chamber heard estimates from people detained on the meadow that there was a total of anywhere from 900 to 2,000 prisoners held captive there.[122] According to the Krstic trial verdict, “Between 1,000 and 4,000 Bosnian Muslim prisoners taken along the Bratunac-Konjevic Polje road were detained in the Sandici Meadow throughout 13 July 1995.”[123] The Krstic trial chamber bases this estimate largely on Serbian radio communications allegedly intercepted by the Bosnian Army.

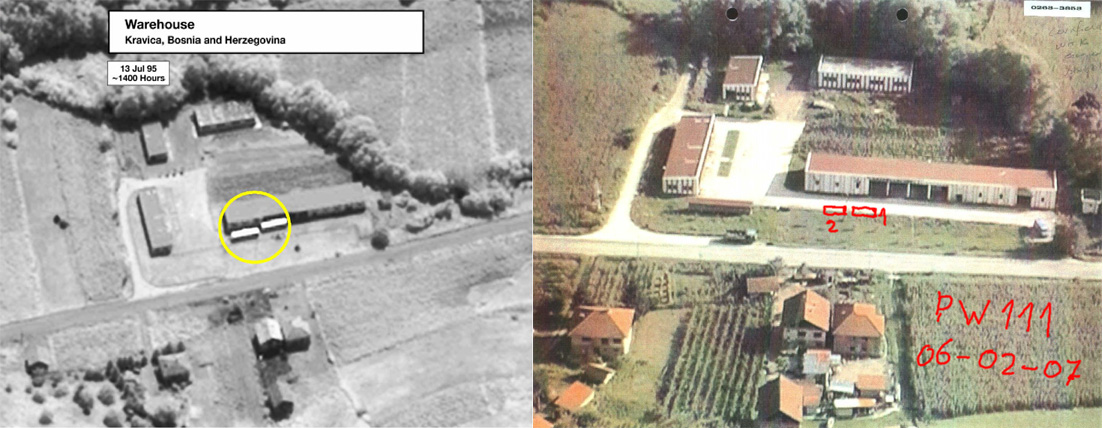

As was the case with the Nova Kasaba football field, there is better evidence than the evidence relied upon by the Tribunal. Here too the United States took an aerial reconnaissance picture of the meadow on the afternoon of July 13th.

Again, according to the CIA’s estimate there are approximately 400 prisoners visible in this photograph.[124]

Yet again, we can corroborate the CIA’s findings by overlaying the photograph in Google Earth and measuring the ground space occupied by the prisoners, and we can see that they’re occupying approximately 478 square meters of ground space.[125]

It is important to note that busses can be seen parked on the road by the meadow, and in another reconnaissance photo taken at the same time; two busses can be seen parked in front of the Kravica warehouse. It is clear from the photographs that the transfer of prisoners from Sandici Meadow to Kravica warehouse was underway when the photographs were taken.

The ICTY’s lead Srebrenica investigator, Jean-Rene Ruez testified about the reconnaissance photographs in the Popovic trial saying, “We knew from the Witness 37 that he was taken there by bus, before being taken inside this east part, and the picture, the aerial picture dated 13 July, shows that at that moment, just at that moment, two buses were parked in front of this east part of the warehouse.”[126]

Witness 37 testified under the pseudonym PW-111 in the Popovic trial, and he did indeed testify that “two buses arrived [at the meadow], and they awaited us on the asphalt road. They made a selection. They didn’t get everybody at the same time. This officer came, the one who stood in front of us with a knife, and he said, ‘You, you, you, come out. Go down to the asphalt road and get on buses.’ I was among them. He selected me, too.”[127]

During his testimony PW-111 marked a photograph showing where the busses that brought him and the group of prisoners he was with to the warehouse were parked and, as you can see below, it corresponds exactly to aerial reconnaissance photograph.[128]

Most importantly, PW-111 testified that the prisoners he arrived with were the

first ones to arrive at the warehouse.[129] And although he wasn’t exactly sure how long the process of transporting

prisoners from the meadow to the warehouse lasted, he estimated that it took an

hour and a half to two hours.[130]

Another survivor of the Kravica warehouse massacre testified that he was not

brought from the meadow to the warehouse until 4:00 or 5:00 PM.[131]

Given that the distance from the meadow to the warehouse is only 1.2 kilometers; if the busses seen in the aerial reconnaissance photograph are the same busses that brought PW-111 to the warehouse, and if PW-111 was among the first to arrive at the warehouse, and if it took a couple of hours to bring the rest of the prisoners from the meadow to the warehouse that would mean that at 2:00 PM when the reconnaissance photos were taken that the transfer of prisoners had just begun and that most of the prisoners would have still been at the Sandici meadow.

The Tolimir Trial Chamber at the ICTY, “finds beyond reasonable doubt that members of the Bosnian Serb Forces killed between 600-1,000 Bosnian Muslims at Kravica Warehouse on 13 and 14 July 1995.”[132] The Popovic trial chamber “concludes that at least 1,000 people were killed in Kravica Warehouse”.[133]

The problem with those findings is that the reconnaissance pictures indicate that there weren’t enough prisoners at Sandici meadow for that many prisoners to have been sent to the warehouse. If there were only 400 prisoners on the meadow when the transfer of prisoners was just getting underway at 2:00 PM, then it is extraordinarily unlikely that 1,000 prisoners could have been sent from the meadow to the warehouse.

The Kravica Warehouse is a finite space. The total floor space of the two rooms of Kravica warehouse where the prisoners were held is 589.5 square meters; 262.5 square meters in the west room, and 327 square meters in the east room.[134] Therefore, we can estimate that the number of prisoners who could have been seated on the floor of Kravica warehouse is somewhere in the region of 600 or 700 men if the warehouse were empty, which it wasn’t.

The warehouse was in use at the time of the massacre and part of the floor space was occupied by the material being stored inside of the warehouse. One of the men who survived the massacre testified that inside the room of the warehouse where he was sitting there were containers, an old wire fence, and a dilapidated old car that were all being stored inside of the warehouse.[135]

Aleksandar Tesic, who served as secretary of the municipal Secretariat for National Defence in Bratunac, saw the warehouse on July 14th after the executions had ended and according to his testimony, “I figure there must have been at least between 200 and 300 bodies lying there piled about a metre and a half high. At first I thought it was firewood stacked up against the wall when I first cast a glance in that direction, and then I realised what it was. So it really left a horrible impression upon us.”[136]

When asked how many people had been killed at Kravica Warehouse, Momir Nikolic, the assistant chief of security and intelligence for the Bratunac Brigade of the Bosnian Serb Army, testified for the Prosecution that “I never really learned the exact number of people who were killed. But the assessment was several hundreds of them.”[137]

According to Prosecutors, “some 500 to a thousand people were killed” at Kravica Warehouse.[138] Based on the number of people present at Sandici meadow at 2:00 PM, and based on the size of the warehouse it would seem that 500 is at the upper end of any estimate that can be considered plausible.

Given that some 500 prisoners arrived at Nova Kasaba between 2:00 PM and 7:00 PM we may assume that the situation at Sandici Meadow was similar, and that several hundred prisoners who had not been sent to Kravica warehouse were sent onward to Bratunac together with the prisoners from Nova Kasaba and the men separated at Potocari.

Prisoners Sent from Bratunac to Zvornik

As stated earlier, the prisoners were initially sent to Bratunac on the 12th and 13th of July, and then they were sent onwards various facilities in the Zvornik municipality where they were executed.

According to the ICTY Prosecution, some 6,000 prisoners were sent to Zvornik and killed.[139] This is a highly improbable estimate for a number of reasons.

We know from the missing persons reports that 1,487 men were captured among the refugees at Potocari. We know from the testimony of Malinic and Subotic that approximately 1,100 prisoners were held at Nova Kasaba football field, and we’re assuming that several hundred prisoners were sent from Sandici Meadow to Bratunac. Our estimates to this point total about 3,000 prisoners who would have been sent from Bratunac to Zvornik.

Our hypothesis that 3,000 prisoners were sent to Zvornik is confirmed by Vinko Pandurevic’s July 18, 1995 combat report.

Pandurevic, in his capacity as the commander of the Zvornik brigade of the Bosnian-Serb Army, wrote that “It is inconceivable to me that someone brought in 3,000 Turks of military age and placed them in schools in the municipality, in addition to 7,000 or so who have fled into the forests. This has created an extremely complex situation and the possibility of total occupation of Zvornik in conjunction with the forces at the front. These actions have stirred up great discontent among the people and the general opinion is that Zvornik is to pay the price for taking of Srebrenica.”[140]

We know that the buildings in the Zvornik municipality that were used to house the prisoners had a combined floor space of 1,866.91 square meters because their blueprints have been tendered into evidence at the ICTY.[141]

We also know the approximate number of busses and trucks that were used to transport the prisoners from Bratunac to Zvornik. In fact the number of busses that were used to transport the prisoners isn’t even in dispute.

When Judge Vassylenko handed down the judgment in the Blagojevic & Jokic trial he said, “On the morning of 14 July, a convoy of approximately 30 buses filled with Bosnian Muslim men left Bratunac for Zvornik. Members of the Bratunac Brigade served as an escort for this convoy. The Bosnian Muslim men were taken to various temporary detention centres in Zvornik municipality, including Grbavci school, the Petkovci school, and the Pilica school. Between 14 and 16 July, the men were blindfolded, put on buses, and taken to nearby fields where group and group of helpless terrified Bosnian Muslim men were executed.”[142] The number of 30 busses is repeated again in the judgment.[143]

When Vujadin Popovic testified in the Karadzic trial he said, “I formed a convoy of 30 buses, one trailer-truck, and one longer bus.”[144] Popovic was the chief of security for the Drina Corps of the Bosnian-Serb Army and it was his job to establish the convoy.

Even the Bosnian-Muslim survivors give similar estimates to those given by Popovic and the ICTY trial chamber. Witness Kemal Mehmedovic, testified that “there were at least 30 vehicles moving along that road” in the convoy headed to Zvornik.[145] Protected Prosecution witness PW-110, who survived execution at Orahovac testified that “there must have been at least 20 vehicles in the column, as it was very long, even 30.”[146]

In addition to the main convoy led by Popovic that transported prisoners from Bratunac to Zvornik on the afternoon of the 14th, there was a smaller convoy led by Lt. Jasikovac that took prisoners from Bratunac to the Orahovac School in Zvornik late on the night of the 13th.

The number of busses in the smaller convoy ranges from about six to nine. Protected prosecution witness PW-169 (a Bosnian-Muslim who survived execution at Orahovac) testified in the Popovic trial that there were six buses in the smaller convoy.[147] When asked how many busses were in the convoy, Dragoje Ivanovic, a military policeman from the Zvornik Brigade testified that there were “perhaps seven or eight, maybe nine, but I’m uncertain.”[148]

The 30 standard busses, the trailer truck, and the long bus led by Popovic together with the six to nine buses led by Jasikovac puts us in the neighborhood of about 40 busloads of prisoners that were transported from Bratunac to Zvornik altogether.

Not only do we know that there were about 40 busloads of prisoners, but we know approximately how many prisoners each bus could hold. According to the findings of the Tolimir Trial Chamber “Each bus could accommodate 40 to 50 people.”[149] Witness Mane Djuric saw the convoy, and although he didn’t count the number of buses he testified that each bus looked like it could hold about 45 people.[150]

If we multiply 40 busses by 45 people per bus we get 1,800 as the approximate seating capacity of the busses that were used to transport the prisoners from Bratunac to Zvornik.

Protected Prosecution Witness N, a Bosnian-Muslim who survived an execution, testified in the Krstic trial that the buses were very crowded. He said that on his way to Zvornik he could see that on the bus ahead of him “One could see through the windows that there was a whole line of people standing in the aisle, that there wasn’t enough room for everyone to sit down.”[151]

Given the scarcity of fuel during the war, it is very likely that the Bosnian-Serbs would have crammed as many prisoners as physically possible onto each bus in order to reduce the number of busses required to transport the prisoners and conserve fuel.

We know that approximately 40 busloads of prisoners were taken from Bratunac to various facilities in Zvornik. We know that the combined floor space of the buildings in Zvornik was 1,866.91 square meters, and we know that Pandurevic’s estimate is that there were 3,000 prisoners.

3,000 prisoners divided by 40 buses equals 75 prisoners per bus (which is 167% of the normal seating capacity of each bus), and 3,000 prisoners divided by 1866.91 square meters equals 1.61 prisoners per square meter. The conditions would have been extremely crowded, but it’s possible and the math adds up. The ICTY prosecutor’s estimate of 6,000 prisoners killed in Zvornik is extremely unlikely.

Another indicator that there were 3,000, and not 6,000, prisoners is the transcript of the BH Presidency session of the 11th of August, 1995.[152] In that transcript Izetbegovic is talking about an intercept where “two Chetniks” are talking about the massacre of 3,000 people from Srebrenica.

Izetbegovic is quoted in the transcript as saying: “The number of killed people is most probably somewhere around 3,000. This is the figure that has been mentioned from the first day there. In fact we intercepted a very clear Chetnik telephone conversation, obviously authentic, where they say: ‘there was a massacre here yesterday. It was a real slaughterhouse’. So, how many, 300? ‘No, add another zero’, said one Chetnik to the other. He was talking about the massacre of 3,000 people - one Chetnik to another.”

Izetbegovic emphasized that “This is according to the Chetnik information, which in this case could be the most reliable. This is their information, where they speak to one another about what happened. The man who took part in the massacre talked about it. He was telling someone else. This conversation is available if you are interested. It is one month old. This is it, more or less.”

Zvornik is the

only place where that many people could have been killed. There were never that

many people assembled in any of the other places where prisoners were executed.

Zvornik is the only place where the massacre of 3,000 people was possible, and

the number corresponds exactly to the number that Pandurevic and our estimates

say there was.

Calculating the Number of Executed Prisoners

There were about 3,000 prisoners who were taken to Zvornik and killed. Another group of up to 500 prisoners was killed at Kravica Warehouse, and if we take the ICTY prosecution at its word about 400 prisoners were captured and killed in other circumstances. This puts the number of prisoners that the Bosnian-Serbs executed at about 3,900, which is less than half of the 8,000 that have been alleged.

Accounting for the Rest of the Missing and Dead

If the Bosnian-Serbs executed approximately 3,900 prisoners, then what happened to the rest of the 7,661 people on the Prosecution’s list of missing and dead? The short answer – they died on the battlefield trying to fight their way across Serbian territory en route to Tuzla.

There is no dispute that the column of men that broke out of Srebrenica was a legitimate military target. The ICTY prosecutor’s own military expert readily admitted that the column did “qualify as a legitimate military target.”[153]

Even the prosecutors themselves acknowledged the military character of the column. Senior prosecutor Peter McCloskey told the court point blank, “It was a military column. You don’t see any war crimes being charged on the attack of this column. And the head of this column was a military column and it did a hell of an attack on 16 July and many Serb soldiers were killed.”[154]

We know from numerous credible sources within the UN and among the survivors that the column suffered several thousand combat losses, which pretty well accounts for the number of missing and dead that were not executed.

Carl Bildt served as the European Union co-Chairman of the International Conference on the Former Yugoslavia. He was the Prime Minister of Sweden 1991-1994, Co-Chairman of the Dayton Peace Conference and subsequently the first High Representative in Bosnia-Herzegovina. He wrote in his book Peace Journey that “when we eventually, in early August, began to understand what had really happened the picture became even more gruesome. In five days of massacres, Mladic had arranged for the methodical execution of more than three thousand men who had stayed behind and become prisoners of war. And probably more than four thousand people had lost their lives in a week of brutal ambushes and fighting in the forests, by the roadside and in the valleys between Srebrenica and the Tuzla district, as the column was trying to reach safety.”[155]